Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum: The First Same-Sex Couple in History

Or Just Twins? A Detailed Investigation.

- Editorial team

Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum were two men who served at the pharaoh’s court in Ancient Egypt. Their title was unusual: they were supervisors of the king’s manicurists. They became known not for their official duties, but for the nature of their burial. They were interred together in a single tomb.

Some scholars argue that this may represent the earliest documented same-sex couple in history. In Egyptian art, there are few comparable examples in which two men are depicted with such explicit tenderness.

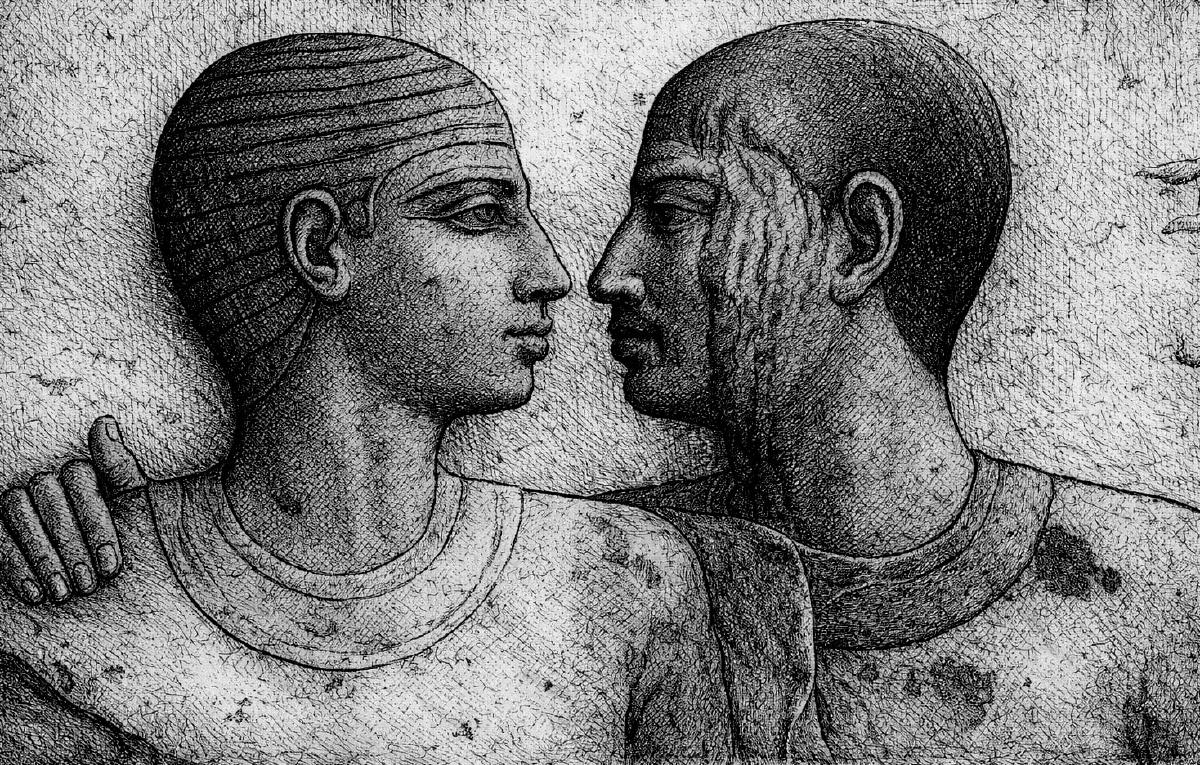

The tomb reliefs show Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum standing nose to nose — a conventional way to depict a kiss at the time — as well as embracing and holding hands. In the visual culture of that period, this degree of intimacy was generally reserved for a husband and wife. This has therefore been treated as the central evidence for a romantic interpretation.

However, this reading is contested. Critics note that the tomb also includes depictions of wives (yes, both men had them) and their children. On this view, Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum may not have been lovers, but brothers — possibly even twins.

In this extended article, we examine who Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum were, when they lived, what is depicted on the walls of their tomb, and whether it is defensible to describe them as a couple. We proceed step by step — scene by scene — as if on a guided tour.

The Discovery and Layout of the Tomb

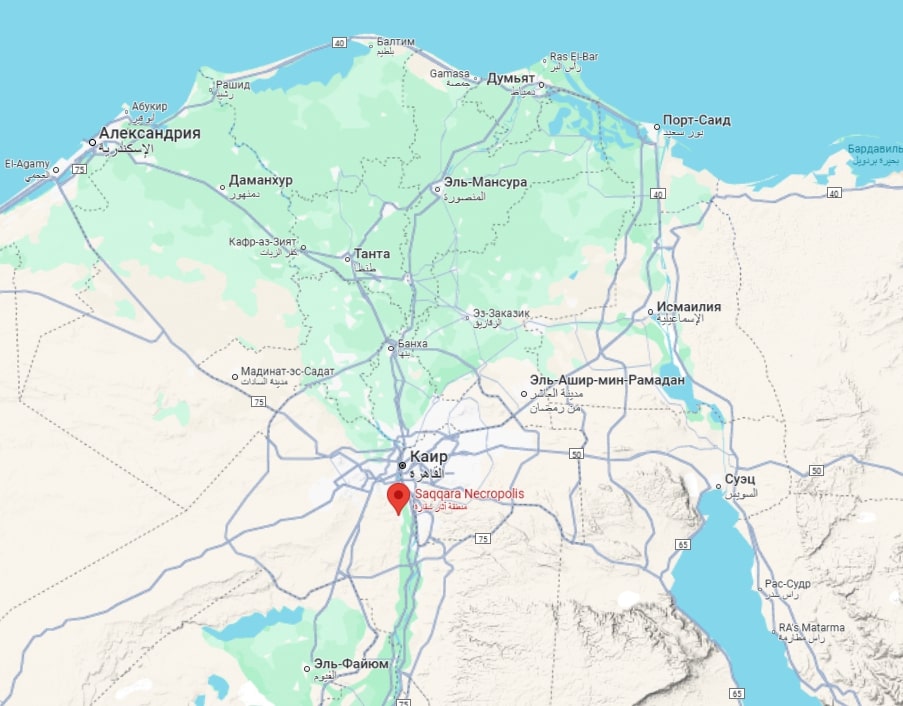

The tomb was discovered in 1964 in the Saqqara necropolis. The Egyptologist Ahmed Moussa found it while clearing a passage leading to the pyramid of Pharaoh Unas.

Once the shaft had been cleared, Mounir Basta, the Chief Inspector of Lower Egypt, chose to descend himself. With a worker and a kerosene lamp, he made his way down a narrow staircase into the darkness. The stairs opened into a small offering chamber. Its walls were covered with inscriptions — entirely typical for a monument of this kind. The most significant feature, however, lay deeper inside.

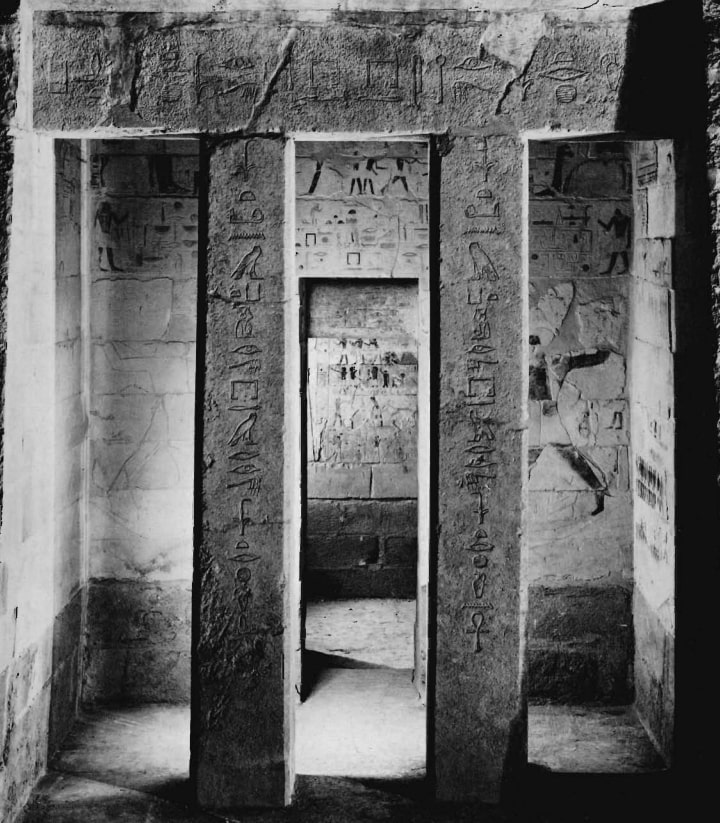

Between two false doors — a symbolic “door” carved into a tomb wall, intended to allow the spirit to pass — the stone was carved with the figures of two men embracing. Basta was astonished. By his account, he had never seen anything comparable in any tomb before.

The precise date of the tomb’s construction remains disputed. On stylistic grounds, it is usually assigned to the second half of the Fifth Dynasty — the reign of Pharaoh Nyuserre or Menkauhor. No human remains were found inside.

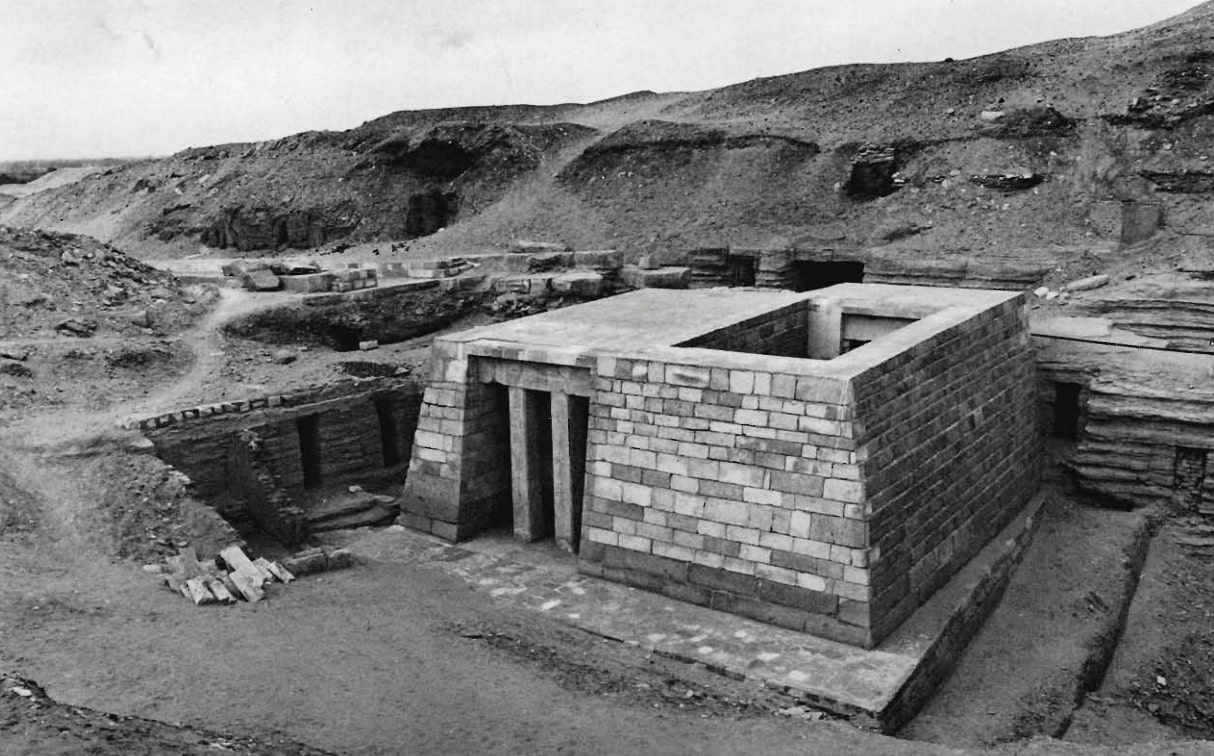

Researchers generally argue that the tomb was built in stages. Initially, two chambers were cut into the soft limestone of northern Saqqara. Later, a mastaba — a rectangular structure with a flat roof and sloping sides — was built above them. A burial shaft was typically located beneath a mastaba. The work appears to have proceeded intermittently, advancing as the tomb owners were able to finance it.

In antiquity, the tomb was looted. The limestone sarcophagi, carved and concealed beneath the mastaba, were damaged. In the late 1970s, German archaeologists carried out a restoration, and in the 1990s the tomb was opened to visitors.

The Era and the Political - Religious Background

The Fifth Dynasty ruled Egypt during the Old Kingdom — roughly from 2504 to 2347 BCE. Over these one and a half centuries, the pharaohs not only consolidated their authority but also substantially reshaped Egypt’s religious landscape. A central role was assumed by the cult of the sun god Ra. From this period onward, nearly every ruler built temples in his honor, and devotion to Ra became a matter of state policy.

One of the dynasty’s most prominent pharaohs was Nyuserre. He came to power only a generation after the construction of Khufu’s Great Pyramid. Historians often place him among the major builders of his era; under his rule, according to a widely held view, the cult of Ra reached its peak.

Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum lived within this broader context of religious expansion and intensive state building.

Who They Were: Social Status and Court Titles

Hieroglyphic inscriptions identify Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum as “overseers of the manicurists of the king’s palace.” The profession was represented by a distinctive hieroglyph — an animal paw with extended claws. These officials supervised the care of the pharaoh’s hands and belonged to the narrow circle of people permitted to touch the ruler.

Preparing the king for public appearances required coordinated work by many specialists. The pharaoh’s external appearance was managed by servants organized into workshops, each with its own hierarchy. In addition to manicurists, for instance, the court employed staff who reported to officials titled “Keeper of the Headdress”; they were responsible for the ruler’s wigs and headcloths.

Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum also held additional titles, including: “Keeper of Secrets,” “Known to the King,” “Trusted Man of the King,” “Keeper of the King’s Property,” “One Who Is Loved by His Lord,” “Priest of Ra,” “Cleaner of the Enduring Places of Nyuserre” (that is, a priest who also performed ritual cleaning), and “One Who Purifies the King.”

They were integrated into a wider network of senior courtiers. One such figure known from the sources is Ptahshepses: first a “Keeper of the Headdress,” and later a vizier who oversaw the construction of pyramids and temples. Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum also appear in his tomb, and he was likely their superior.

Having a separate tomb was a privilege granted to very few. Such monuments were built by royal command or with the approval of an influential priest. They required substantial resources and functioned as an exceptional marker of status.

Both men were married and had large families. Khnumhotep’s wife was Khenut; they raised at least five sons. Niankhkhnum was married to Khentikawes; their household included three sons and three daughters.

It is not known how long either man lived, or who died first. Nevertheless, many researchers suggest that Khnumhotep died earlier. Several details are cited in support: the epithets attached to his name, the style of his beard, and the fact that in the banquet scene only Niankhkhnum’s wife appears nearby. It was therefore likely Niankhkhnum who supervised the tomb’s final decoration.

The Kinship Hypothesis: “Brothers” and “Twins”

In 1979, one of the first scholars to study the tomb, Mounir Basta, made the following observation:

“This scene [of the embracing men] is repeated on two other walls… The importance of discovering this tomb is connected precisely with this unique scene. The inscriptions in the tomb give us no answer to the question of the relationship between these two deceased men. Were they brothers? Were they father and son? Or were they two officials of the royal palace who enjoyed a warm friendship in life and wished to preserve it after death in the afterlife?”

— Mounir Basta, one of the first researchers of the tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep

Those who argue that Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep were relatives rather than a couple usually begin with how they interpret the closeness shown in the tomb scenes. A common proposal is that the men were twins. This view was advanced, for example, by Oxford professor John Baines. In his 1985 article Egyptian Twins, he proposed a broader model for how twinship may have been understood in Ancient Egypt, and suggested that such kinship could account for the exceptional attachment depicted between the two men.

Because no direct Old Kingdom evidence for twins has survived, Baines drew primarily on later material. He discussed a pair of men named Suti and Hor, shown together on a stela from the New Kingdom (roughly 1,000 years later), and argued that they were “undoubted twins.” Baines wrote:

“The stela of Suti and Hor from the reign of Amenhotep II seems to contain the only unambiguous reference to twins or multiple births from dynastic Egypt… The unusual language of this stela at first appears to confirm their ‘undoubted twinship,’ since they are called snw (‘brothers’), and Hor says: ‘he came forth with me from the womb on the same day.’”

— John Baines, on the stela of Suti and Hor

However, even this example does not fully resolve the uncertainty. The wording of the joint inscription of Suti and Hor permits multiple interpretations and remains ambiguous overall. The text does not explicitly state a biological relationship, and the word sn — often translated as “brother” — can also be used in the sense of “close friend.” (Note: in Egyptian texts, kinship terms can function as social terms of closeness, not only literal family ties.)

The claim that they “came forth from the womb on the same day” appears to emphasize parity. It may refer to being born on the same day, but not necessarily to the same mother. Additional parallels have also been noted. Both men held the same position — supervisors of construction work — and their names were associated with gods (one with Seth, the other with Horus). Yet in Egyptian mythology, these gods were not considered twins.

Professor David O’Connor of New York proposed a more unusual hypothesis: the men may have been conjoined twins — that is, physically joined bodies. In his view, the artists used emotional language and even sexual imagery to convey an exceptional bond. At the same time, he acknowledged that no wall scene depicts their bodies as physically joined.

The Egyptologist Richard Parkinson also drew attention to the similarity of their names and allowed that they may have been brothers. However, in Ancient Egypt adults could change their names later in life, so this point is not decisive. In conclusion, Parkinson offered a warning: “the danger is that people want to find positive (homosexual) images in the past, and for a modern European it is very hard to resist the temptation to read the images as homoerotic.”

Because many scholars at the time favored the “brothers” or “twins” explanation, the burial place came to be known as the “Tomb of the Brothers.”

The “Twin” Model: Equal in Status?

The “twin” hypothesis raises an obvious difficulty: several tomb scenes appear too intimate to be explained by kinship alone.

The Egyptologist Jean Revez has proposed that the two men may not have been biological brothers, but symbolic “twins” — individuals aligned in rank, influence, and worldview. He points to the word sn, commonly translated as “brother”, but broader in meaning. Depending on context, it can refer to a friend, a beloved, a spouse, a colleague, an ally, or even a co-ruler. On this reading, the emphasis is not on blood relation, but on equality and spiritual closeness.

In this sense, sn may be understood as an alter ego — a “second self”: someone who shares the same values and holds comparable social standing.

Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep carried the same official title. In the tomb’s paintings and reliefs, they are presented as strictly equal: neither dominates, and each receives the same offerings. Such symmetry is uncommon in Egyptian burial art, where status was typically signaled through differences in figure size, position within the composition, or the frequency of depiction.

The First Same-Sex Couple?

The researcher Greg Reeder argues that the question of who Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep were should be addressed less through conjecture and more through the images themselves. His central method is iconography — the visual language of ancient Egyptian art. To infer what the artists intended, he compares the tomb scenes with other representations from the same period.

In doing so, he draws on Nadine Cherpion’s study Conjugal Affection and Representation in the Old Kingdom (1995). Cherpion compiled and analyzed depictions of married couples from the Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Dynasties, identifying the poses, gestures, and compositional patterns used to communicate physical intimacy between husband and wife.

When the tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep is set alongside Cherpion’s examples, the two men appear to follow the same visual conventions that were typically reserved for a married couple.

It is true that Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep had wives and children — for powerful officials in Ancient Egypt, this was more typical than exceptional. Yet in scenes that foreground bodily closeness, they are depicted not with their wives, but with each other. The wives do appear elsewhere, but those scenes do not include the same established markers of intimacy used to represent a marital pair.

This is particularly clear in the offering hall: it contains no scenes featuring the wives at all. For Reeder, this arrangement indicates the tomb’s primary focus — the bond between Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep themselves.

Let’s walk through the tomb.

Entrance

At the entrance — on both sides of the doorway — their names and titles are inscribed. Both men are assigned the same ranks: “Chief Manicurist,” “King’s Acquaintance,” “Trusted Man of the Pharaoh,” and “Overseer of the Manicurists in the Palace.” On the front wall of the entrance, two figures are shown: Niankhkhnum on one side and Khnumhotep on the other. The reliefs are nearly identical, differing mainly in the names.

Immediately beyond the entrance, the facing walls depict a marsh-hunting scene typical of Egyptian funerary contexts — a symbol of fertility and of continued life after death. Niankhkhnum is shown hunting birds. His children observe the scene, while his wife holds a lotus flower in her hand. On the opposite wall, Khnumhotep appears with a spear, striking two fish. His wife and children stand nearby; his wife likewise inhales the scent of the lotus.

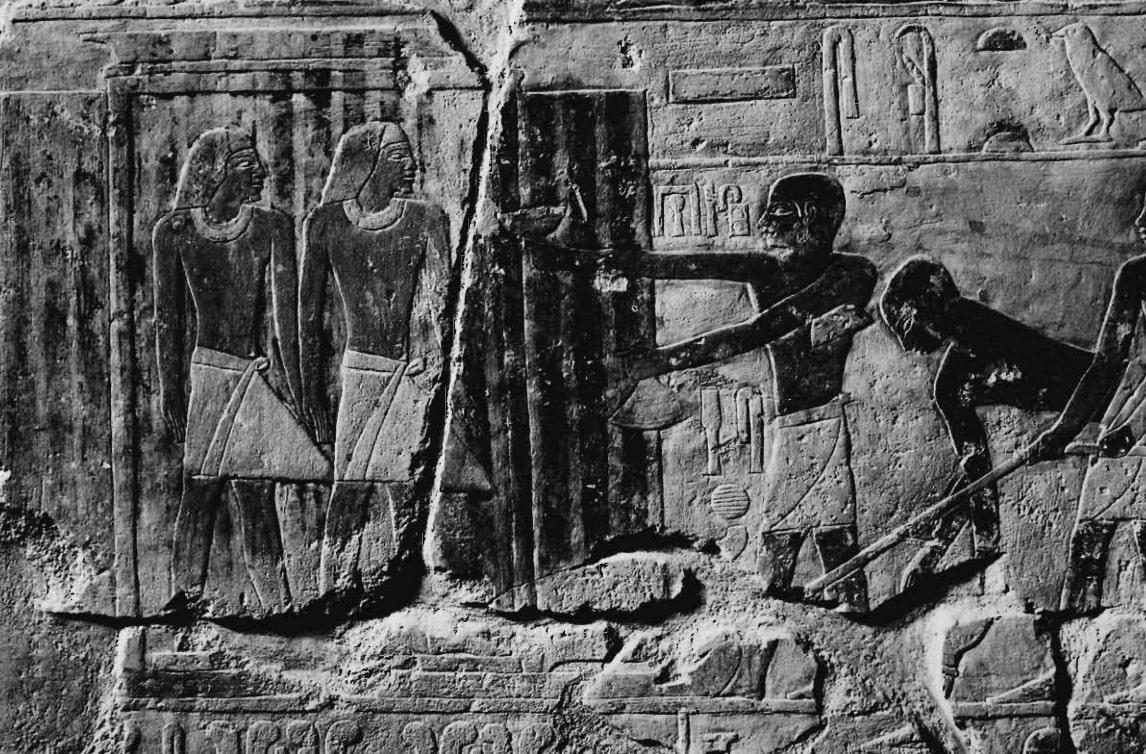

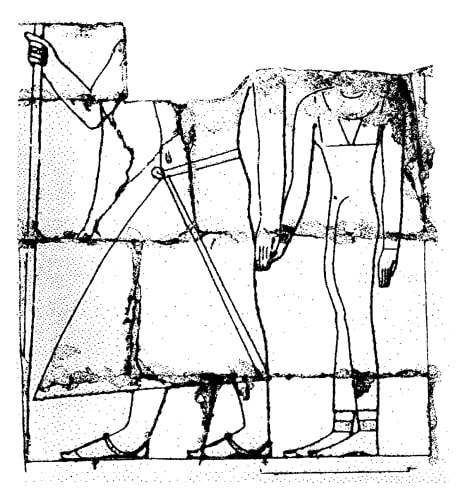

Farther inside, on either side of the second doorway, a scene depicts the transport of statues of the deceased. One element is especially notable: the two men are shown walking while holding hands. This sculptural motif was most commonly used to depict heterosexual married couples.

For example, a comparable statue in the image above — showing a man and a woman holding hands — is kept in the Leipzig Museum under inventory number 3155. It depicts Ni-kau-Khnum and his wife and comes from the chapel of this official’s tomb at Giza.

Moving deeper into the tomb, we again encounter Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep on the eastern wall of the entrance hall. They are seated in a close embrace, presented almost as equals, and receive visitors bringing offerings. As elsewhere in the tomb, Niankhkhnum is placed in front and Khnumhotep behind — a positioning that, in compositions of opposite-sex couples, was typically assigned to the woman.

Comparable iconography — though applied to a heterosexual couple — appears on an offering altar further inside the tomb. This altar belonged to Niankhkhnum’s son, Khamre, and Khamre’s wife, Tjeset. Here, husband and wife sit side by side and receive offerings from their son. Khamre is shown in front and his wife behind; as in the case of Khnumhotep, she extends her arm behind his back and touches his right shoulder.

In front of the depiction of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep is a decree concerning donations. It states that only priests are responsible for protecting the tomb and presenting regular offerings. Neither wives, nor children, nor anyone else is permitted to interfere. The offerings are intended exclusively for Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep, as well as for their fathers and mothers, who were buried in the same necropolis (a cemetery complex). In this context, Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep are again framed in a manner comparable to a married couple.

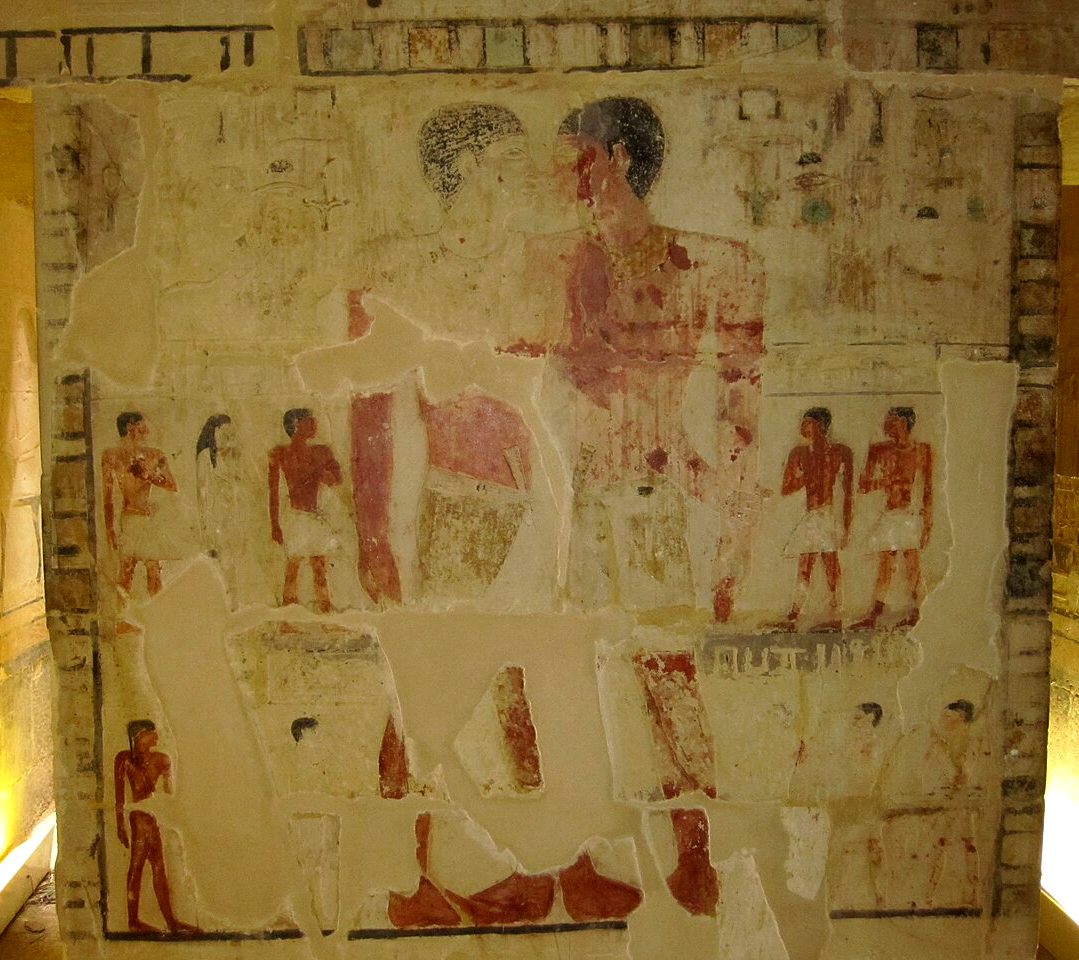

Beneath the seated scene are five horizontal registers (stacked rows in relief art). The third register contains ten figures. They are depicted slightly larger than those above, and this register is central to the case made by scholars who argue that Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep were relatives. Professor Baines and other authors proposed that the man and woman leading the procession could represent the parents of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep.

At the very end of the procession, two men are shown holding hands. The captions beside them identify the figures: Niankhkhnum walks in front, while Khnumhotep follows behind. Regardless of how the first couple relates to the last, the viewer is presented with a visual comparison between two forms of partnership — heterosexual and homosexual.

One detail in the composition is particularly significant. The woman in the first couple and Khnumhotep in the pair with Niankhkhnum are the only figures who do not raise a hand to the chest, but instead hold on to their partner. In this scene, Niankhkhnum leads Khnumhotep by the hand, guiding him deeper into the tomb — as if into the “next world”.

If the viewer turns and moves farther inside, they encounter Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep again on the damaged southern wall of the entrance hall. They are once more shown walking hand in hand, and again it is Niankhkhnum who leads Khnumhotep into the inner rooms of the burial chapel.

This scene parallels compositions found in other tombs. For example, in the tomb of Mereruka, he is depicted walking hand in hand with his wife, Watetkhethor (in the image above): he leads her deeper into the tomb and, as scholars typically argue, toward the marital bed.

The First Vestibule, The Courtyard, The Second Vestibule

In the first vestibule, the reliefs depict scenes of daily life: baking bread, brewing beer, herding goats, building boats, harvesting, sailing (sport), catching birds with nets, and other activities. A legal text appears on the eastern wall.

The courtyard functions as a neutral transitional area. It connects the vestibule to the chambers of the mastaba — a flat-roofed rectangular tomb with sloping sides — and to the southern section of the complex, which was cut directly into the rock.

In the second vestibule, the visitor encounters the names, titles, and portraits of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep. The lintel above the entrance is decorated with a scene of a livestock census. On the side walls, each man is shown beside his wife, framed by offerings drawn from numerous herds.

At the entrance to the rock-cut section of the tomb, above the doorway, the names of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep are carved — and presented as a single name. Both contain the hieroglyph of a vessel associated with the god Khnum. Khnum was not only a potter god, but also the deity who shaped human beings from clay on a potter’s wheel. He was also regarded as a patron of the Nile floods — the source of life.

Both names are theophoric (that is, they incorporate the name of a deity). The name Niankhkhnum (originally written as N(y) ˁnḫ ẖnmw), placed on the right, can be translated as “Khnum lives” or “The god Khnum is alive”. It is written with the vessel sign and the ankh hieroglyph — a symbol of life. The name Khnumhotep (ẖnm ḥtp), placed on the left, means “Khnum is satisfied” or “Khnum is pleased”. Here, the offering hieroglyph is used — a loaf of bread on a table — which conveys peace and satisfaction, particularly in the context of the funerary cult.

The word “Khnum” in Egyptian did not function only as the name of a deity. It could also mean “joined” or “binding”, and later became associated with ideas such as “partners”, “companions”, and “members of the household”. For this reason, the unified writing of the two men’s names above the entrance to the burial chamber may be more than a reference to the god. It may also reflect deliberate wordplay. In that case, the composition could suggest “together in life and in death”.

Researchers cannot determine with certainty when these names were assigned — at birth or later in adulthood. It is possible that they reflected a conscious decision and expressed the bond that developed between the two men.

Below the inscription, on both sides of the doorway, the two men are depicted again. Between them rise large piles of offerings. On the right sits Niankhkhnum; on the left is Khnumhotep, smelling a lotus. In the Fifth Dynasty, this pose is exceptionally rare for men: across roughly 150 years, only three such cases are recorded. In the Old Kingdom, figures smelling a lotus were typically women. In this tomb, the lotus is smelled only by women and by Khnumhotep. This may be an intentional visual strategy. The artists may have emphasized that, within the composition, Khnumhotep in a sense occupies a role usually assigned to a wife.

Front Chamber and Offering Room

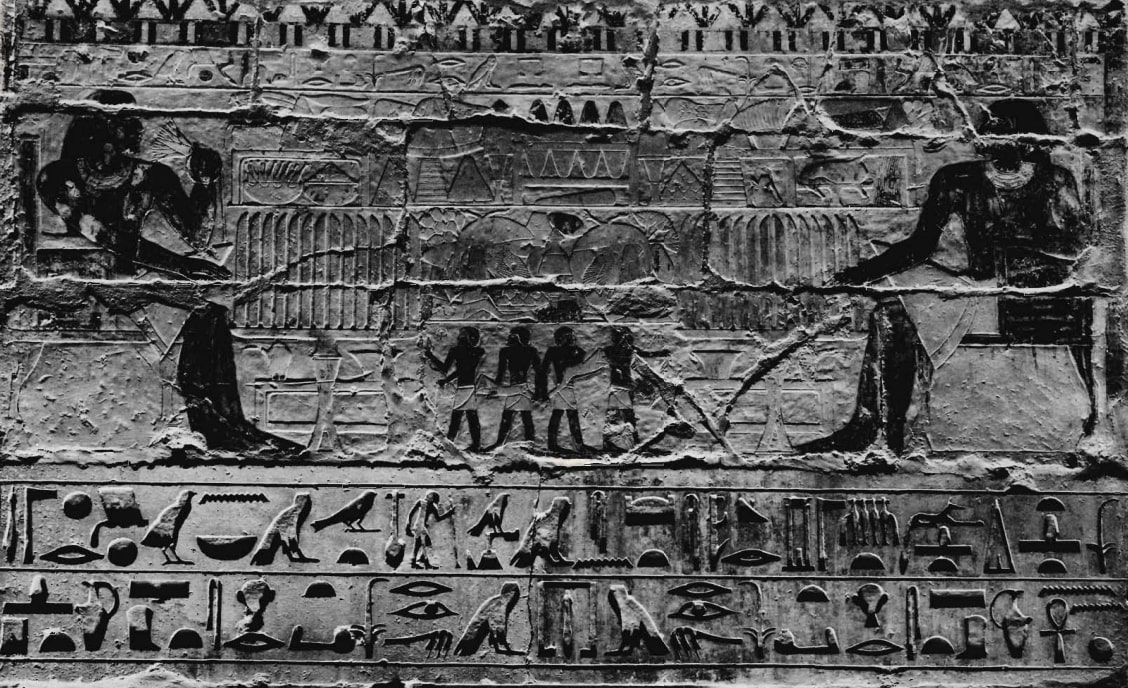

Deeper inside the rock-cut chamber, the southern wall contains a detailed banquet scene. It stands out not only for the number of figures and the density of detail — musicians, singers, and dancers — but also for the modifications made by the artisans during carving.

Behind Niankhkhnum (on the left in the image), his wife was originally depicted. She was seated almost at the same height as he is and appears to have been embracing him. This would have been the only place in the tomb where the wife is shown as nearly equal to her husband in scale. In other scenes, the women are clearly shorter than their husbands — a standard artistic convention for representing wives.

For reasons that remain unclear, the artisans later removed the wife’s figure. As a result, Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep remained the only central participants in the banquet.

Behind Khnumhotep, there is no vacant space that suggests a wife was ever planned. He sits directly against the wall and holds a lotus flower in his hand.

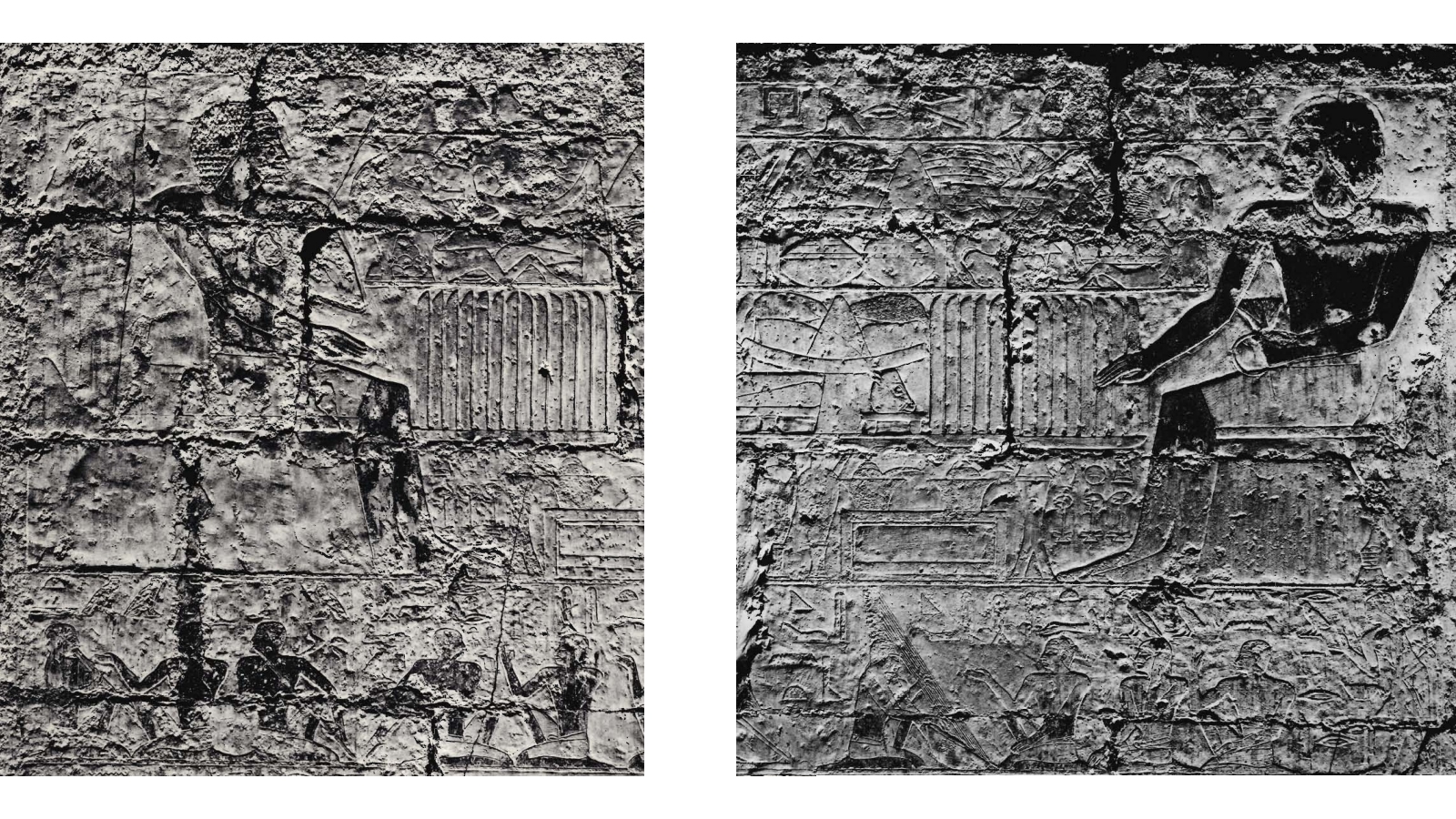

The first clearly intimate scene appears at the entrance to the offering chapel. Niankhkhnum supports his companion’s forearm. Khnumhotep replies by embracing Niankhkhnum: his arm passes behind his partner’s back and grips his shoulder. One embraces, the other supports. This “dialogue” of gestures conveys a strong impression of personal closeness between the two men. Children are shown around them, but the wives are absent.

Comparable compositions appear elsewhere. In the tomb of Kai at Giza, for example, the wife embraces her husband, while their children are depicted on both sides. In the tomb of Ukhhemka (also at Giza), the wife places one hand on her husband’s shoulder while holding his forearm with the other. This is an almost exact parallel to the gestures shown by the men in the tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep.

Inside the offering chapel, archaeologists found two false doors — one for Niankhkhnum and one for Khnumhotep — positioned side by side. Niankhkhnum’s false door had already been almost completely destroyed in antiquity, likely by tomb robbers.

In Egyptian tombs, a false door is not an actual entrance, but a carved relief on the wall. According to Egyptian belief, the deceased person’s ka — their life-force (a key concept in Egyptian religion) — could pass through it into the world of the living to receive offerings. The false door thus served as a symbolic portal between the worlds of the living and the dead. It was often decorated with inscriptions and images and was typically placed on the west wall of the tomb.

Between the false doors is another scene — an embrace. This is the scene the researcher Basta noted in 1964. As in the other reliefs, Niankhkhnum supports his companion, and Khnumhotep embraces him. They face each other, but the pose appears less intimate than the scene at the entrance to the offering chapel. The composition closely resembles — and may deliberately echo — a relief from the slightly earlier nearby tomb of Nefer and Kahay, located along the road to the pyramid of Unas.

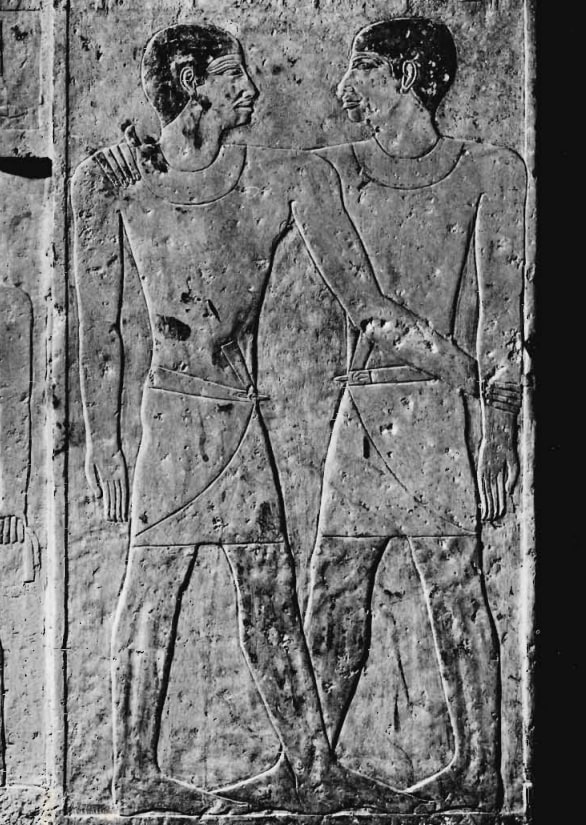

Directly opposite the false doors, on the inner face of the entrance pillar, is the most intimate and emotionally charged scene involving Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep. They stand facing one another. No one else is present — only the two of them.

Here, the men are depicted closer than in any other scene, and even closer than husbands and wives are typically shown — for example, in the tombs of Nefer or Kha-Hay. Their bodies press together so tightly that the knots of the belts at their waists meet, as if to link them symbolically. They look into each other’s eyes, standing nose to nose.

The composition implies that the artist intended to suggest a kiss. In Old Kingdom writing, the word “kiss” could be rendered with a sign showing two noses touching.

***

Historical sources indicate that in Ancient Egypt homosexuality was rarely addressed directly. When it does appear, it is usually framed as a negative judgment of a specific act — anal intercourse — rather than as a general condemnation of emotional or physical closeness between men. Egyptian ideology centered on the conventional family unit: father, mother, and children. This model was treated as the normative ideal and was consistently reinforced in official rhetoric. Even so, the sources occasionally allude to other forms of relationships.

The tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep offers a rare and revealing example of such alternative bonds. Although archaeologists have found indications that other family members were also buried in the chapel, the spatial arrangement and decorative emphasis suggest that the monument was originally conceived primarily for the two manicurists to share eternity together.

A comparison of the full set of intimate scenes shows that their portrayal follows the same artistic conventions used for married couples in Old Kingdom tombs of the 4th, 5th, and 6th dynasties. The visual language applied to the two men is closest to the standard depiction of affection between husband and wife.

Whatever their kinship or biological relationship may have been, the tomb’s imagery points to a strong attachment and, potentially, romantic desire. This iconography departs noticeably from Old Kingdom norms, which is precisely why the tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep remains a singular monument.

🏺 This piece is part of the article series “LGBT History of Ancient Egypt”:

- A Queer Lexicon of Ancient Egypt

- Divine Homosexuality in the Ancient Egyptian Myth of Horus and Seth

- Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum: The First Same-Sex Couple in History

- A Homoerotic Plot in Ancient Egyptian Literature: Pharaoh Pepi II Neferkare and General Sasenet

- Idet and Ruiu: Lesbian Lovers in Ancient Egypt?

- A Possible Scene of Same-Sex Intercourse from Ancient Egypt — The Love Ostracon

- Goddess Nephthys — a lesbian?

📣 Subscribe to our Telegram channel (in Russian): Urania. With Telegram Premium, you can translate posts in-app. Without it, many posts link to our website, where you can switch languages — most new articles are published in multiple languages from the start.

References and Sources

- Reeder G. Same-Sex Desire, Conjugal Constructs, and the Tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep, World Archaeology, 2000.

- Reeder G., Cooney K. M., Graves-Brown C. Queer Egyptologies of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep, in Sex and Gender in Ancient Egypt: Don Your Wig for a Joyful Hour, 2008.

- Simpson W. K., Das Grab des Nianchchnum und Chnumhotep (Book Review), Orientalistische Literaturzeitung, 1982. [Simpson, W. K. - The Tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep (Book Review)]

- Ranke H. Die ägyptischen Personennamen. Bd. 1: Verzeichnis der Namen, 1935. [Ranke, H. - The Egyptian Personal Names]

- Tags:

- Ancient-Egypt