The Execution of the Siamese Gay Prince Rakronnaret (Mom Kraison): Power and a Charge of Treason

The earliest known episode in Thailand’s LGBT history.

- Editorial team

In 1848, the King of Siam (present-day Thailand), Rama III, sentenced his friend - an openly gay prince, Rakronnaret (also known as Kraison) - to death on a charge of treason. He was reportedly placed in a velvet sack and beaten to death with clubs.

India and China preserve evidence of same-sex love dating back as far as 3,500 years, yet sources on Thailand’s queer history are scarce. The case of Prince Rakronnaret is often treated as the earliest documented episode in which same-sex relationships are described explicitly.

In court influence, the prince reportedly ranked second only to the king. His standing was later clouded by allegations of corruption, as well as by his numerous relationships with members of a male theatre troupe that he owned. Rakronnaret did not conceal these relationships.

Why was Rakronnaret executed? Was there a link between his sexual behaviour and the accusations of political treason? Was he punished for both - or only for the suspicion of treason?

The Origins and Early Years of Prince Rakronnaret

Prince Rakronnaret was born on December 26, 1791. He was the 33rd child of King Rama I and the son of Kaeo Noi, a royal consort (a secondary wife / concubine in the Siamese court context). From an early age, he showed an interest in Buddhism, developed a fascination with divination, and became a close friend of the Crown Prince - the future King Rama III.

As an adult, Rakronnaret held several senior posts in the state administration under Rama III. He oversaw ministries linked to the Buddhist monastic order and the palace, as well as an office responsible for the kingdom’s southern regions. He also served as a judge with the highest authority in cases that fell under these institutions.

These roles enabled him to expand his influence, amass wealth, and cultivate an extensive network of connections. By the 1840s, his authority had become sufficiently visible that some courtiers began to view him with suspicion.

Tensions escalated when rumours circulated that Rakronnaret had allegedly entered a conspiracy with secret societies and intended to organise a coup against the king. This cooled Rama III’s attitude toward him - despite their long friendship and the king’s earlier patronage.

How the Investigation Against the Prince Began

The investigation was triggered by a dispute between two men within Rakronnaret’s dependents. One accused the other man’s son of theft. The charge was false, but the accuser hoped that a prison sentence would deprive the young man of the right to inherit his father’s position. The vacancy left by the elderly man could then be taken by the accuser himself.

Using his wealth, the accuser bribed judges and members of the theatre troupe closely associated with the prince and under his protection. This helped secure the desired ruling. An appeal addressed directly to the prince achieved nothing: Rakronnaret left the verdict unchanged.

The elderly father then submitted a complaint to King Rama III. Outraged by what he learned, the king ordered an investigation. The inquiry quickly established that Prince Rakronnaret had confirmed an unjust decision. Interpreting this as a betrayal, the king ordered the inquiry to be expanded and the prince’s broader conduct to be examined as well.

The findings surprised the court. It emerged that the prince not only accepted bribes in exchange for judicial outcomes, but also permitted members of his theatre troupe to take money from both sides in a case. Decisions were issued in favour of whoever paid more.

The Prince’s Theatre Troupe and Its Special Role

The theatre troupe occupied a central place in Prince Rakronnaret’s life. Its actors participated in reenactments of royal rituals. Together with them, the prince imitated the king and his consorts - copying their mannerisms and wearing lavish clothing.

The actors dressed in ruby silk and wore diamond rings, presenting themselves as royal consorts. Both aristocrats and commoners were drawn into the group, and those who refused were threatened with punishment.

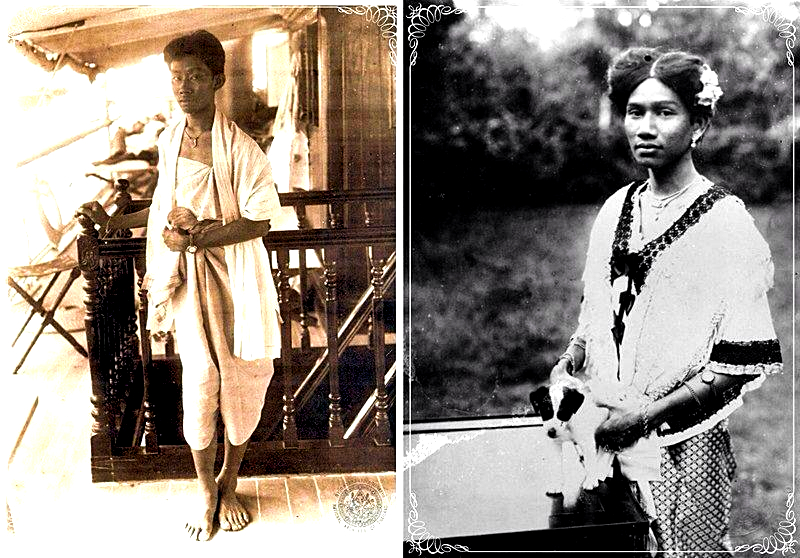

The Siamese self-taught historian K.S.R. Kulap Kritsananon describes the prince seated on an ornate throne shaped like a lion, while the actors, dressed as royal consorts, lined up before him and prostrated themselves in worship. Notably, there were no women in this “retinue” - the roles were performed exclusively by young men.

K.S.R. Kulap Kritsananon noted that the behaviour of the prince and those around him became increasingly provocative over time. The prince eventually stopped living with his wives and children, preferring to spend the nights in the actors’ quarters.

Among the actors, a special place belonged to Ai Huntōng, who played the hero Inao from a popular Javanese tale. Another favourite was Ai Em, who played Princess Bussaba - Inao’s beloved. The prince’s interest extended both to performers of male roles and to those who portrayed women.

Interrogations and Confessions: What the King Learned

The king ordered the actors to be interrogated. According to the official version, they stated that they and the prince practised mutual masturbation, while avoiding penetration. K.S.R. Kulap Kritsananon, however, claimed that the actors confessed that they had been the prince’s lovers (pen sawat - men who held a position analogous to royal consorts). He elaborated on the official record: “the actors confirmed that each of them was in the status of the prince’s lover.” K.S.R. Kulap Kritsananon also clarified that, in his usage, “lovers” referred to men occupying a role similar to that of royal spouses. In his account, the relationships between the prince and the actors included not only mutual masturbation, but also anal sex (len sawat - a term used here for anal intercourse).

In both versions, the first question the king asked the prince was not about treason or corruption. He asked: “You are a high-ranking lord. Do you think it is proper to behave like this [to engage in anal sex (len sawat)]?” He then added: “Second, you hold a high office. Why are you gathering so many officials around you? Are you planning to raise a rebellion?”

Prince Rakronnaret replied that his private life was unrelated to his official duties. He argued that relationships with men did not violate the law. He explained the gathering of his retinue as preparation for the period after King Rama III’s death. The prince also made clear that he did not wish to submit to anyone in the future and, in effect, declared that he did not intend to serve the next monarch - Prince Mongkut, who was expected to inherit the throne.

In addition, the prince named his own potential successor, which finally convinced Rama III that there was a direct threat to his power. A council of princes and ministers confirmed these concerns. They unanimously recommended a death sentence as the only possible solution.

The Verdict Against Rakronnaret and Its Execution

Prince Rakronnaret was convicted of several offences. He was accused of embezzling funds intended to support members of the royal family, as well as donations meant for temples. He was also alleged to have solicited bribes from litigants and from those seeking noble appointments.

The king denounced the prince for arrogance and ingratitude, describing him as a traitor whom he had trusted in his most difficult moments. Rama III said he regretted that his warnings about the destructive consequences of such conduct had been ignored. He repeatedly told the prince that his refusal to live with his wives was harming his reputation. The women regularly visited the Grand Palace and openly complained that the prince cared neither for them nor for his children. Instead, they said, he was “madly in love with his actors”.

Rama III compared the situation to a Qing-dynasty Chinese emperor known for his devotion to opera and for intimacy with both men and female prostitutes. At the same time, the king stressed that he had deliberately not forbidden the prince to behave in this way, in order to avoid humiliating him publicly before other members of the family.

The chronicles agree that long before the open conflict, the monarch was aware of both the prince’s sexual preferences and his corruption:

I have known this for a long time, and I would like to stop you by warning you that such shameful behaviour, like that shown by the lord from Beijing, is unacceptable. I would like to tell you that everyone already knows. I would like to warn you not to do it. It is neither virtuous nor refined. But if I had done so, I feared that my warning would leak out and disgrace you before your relatives and friends. Besides, you would have accused me of deliberately humiliating you in front of those close to you.

— King Rama III on Prince Rakronnaret’s conduct

The king acknowledged that he had taken no action for a long time. However, he concluded his speech with a sharp denunciation of the prince for building a personal inner circle and making clear claims to the throne. He argued that such behaviour, as he put it, “would be accepted by neither any human being nor even an animal”.

In response, the prince again insisted that his private life did not affect the performance of his duties. The king rejected this explanation, stating that the prince’s immoral conduct cast a shadow not only on him personally, but on the royal family and on the reign as a whole.

The monarch stripped Prince Rakronnaret of all titles and sentenced him to death. At the time of his execution, the prince was 56 years old.

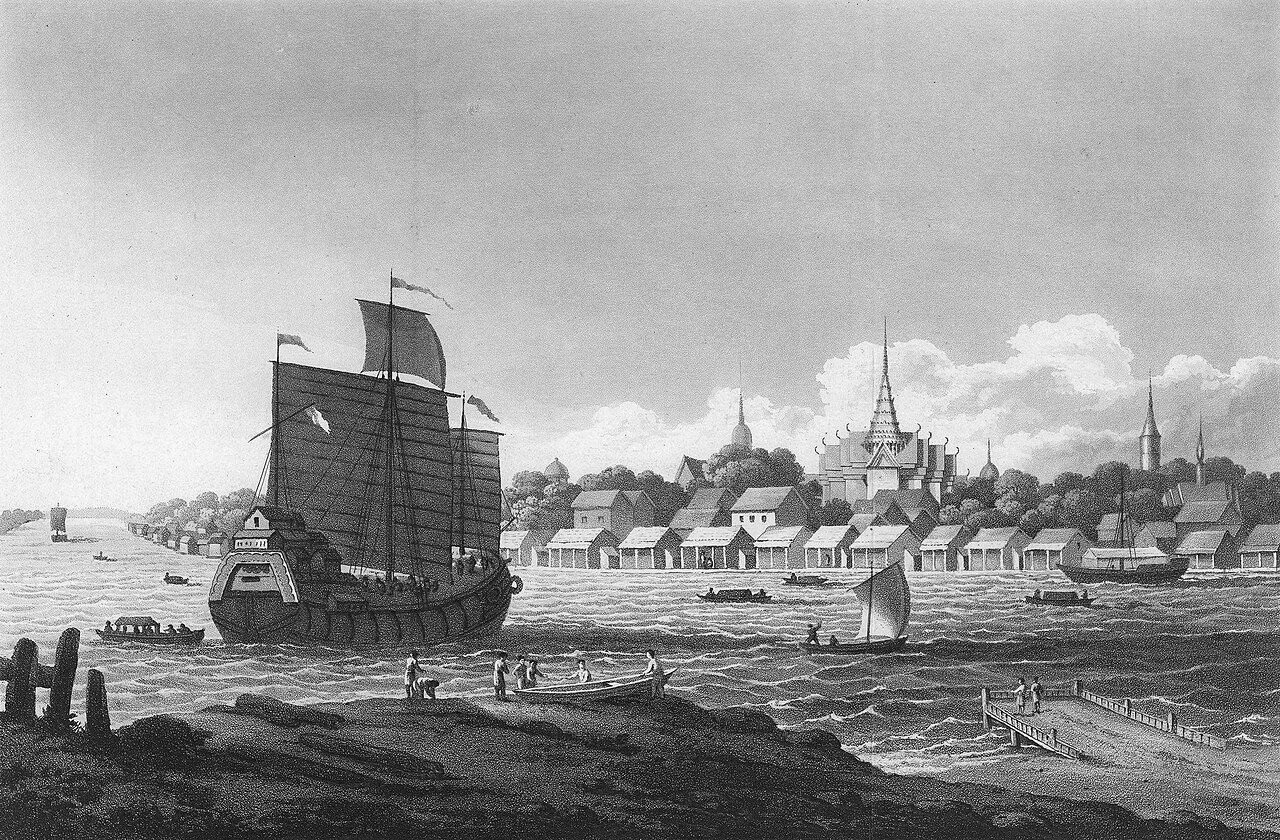

On 13 December 1848, the sentence against Prince Rakronnaret was carried out at Wat Pathum Khongkha Ratchaworawihan Temple (formerly known as Wat Sampheng) in Bangkok. In accordance with the traditional method of execution for members of the royal family, he was placed in a velvet sack and beaten with sandalwood clubs. He was the last member of the royal family to be executed by this method. Kulap adds that before the execution the prince was flogged 90 times.

Three of the prince’s accomplices were also executed - a judge, his deputy, and an official from the royal palace service. They were beheaded.

Who Rewrote Rakronnaret’s History - And How

It is important to consider the extent to which censorship may have shaped the sources that survived. Accounts of this case appear in four different documents, yet only three were published.

The most detailed report - never published - was written by the son of the official who led the investigation. By order of King Chulalongkorn (reigned 1868–1910), he compiled chronicles of the first four reigns of the Chakri dynasty. However, the third part, covering the reign of Rama III, was published only in 1934 - more than 60 years later. The delay was explained as a fear of offending Prince Rakronnaret’s still-living relatives.

The royal family sought to protect the dynasty’s reputation. For this reason, the original manuscript and the published version appear to differ, although the scale of the edits cannot be established: the original remains inaccessible.

A third source came from a foreign author. In 1869, the American missionary Samuel Smith published an article in which he noted the prince’s exceptional learning in Buddhist, Brahmanical, and astronomical traditions. At the same time, he claimed that Rakronnaret used his position to expand his personal power and increase his wealth. Smith did not mention the prince’s sexual relationships - likely because he lacked information, or because he chose not to address the topic.

A fourth source appeared in 1900 in the periodical Sayam Praphet. It was a version of the case prepared by the journalist K.S.R. Kulap Kritsananon. His text was longer and more detailed than the official account. It is possible that K.S.R. Kulap Kritsananon had access to the original manuscript.

Kulap Krichananon (1834–1921) received an education comparable to that of high-ranking princes. Yet his commoner origins and his reputation as an upstart kept him outside court circles. At the same time, he lived in a manner typical of the elite: he had 12 wives and 16 children.

Motivated by an interest in history, Kulap began to challenge the royal family’s monopoly on interpreting Siam’s past. In 1897, he founded Sayam Praphet, where he published his own research. His essays sparked controversy, especially among members of the royal elite. Kulap also often blended speculation and interpretation into his writing without clearly separating them from official information.

Kulap appears to have gained access to royal manuscripts by chance. During the construction of a new palace for Rama V, the texts were temporarily stored at the residence of one of the princes. Prince Bodin granted him limited access to the library on the condition that the books could not be copied. However, Kulap persuaded the prince to let him take one book overnight, with an obligation to return it in the morning. He then hired assistants who copied the texts at night. Within a year, Kulap had assembled a substantial collection of materials.

Researchers suggest that Kulap may have intentionally altered the published versions of manuscripts to mislead the authorities. He likely aimed to create the impression that his information came from other sources, thereby reducing the risk of punishment for copying royal texts.

It is difficult to determine how closely Kulap’s account of Prince Rakronnaret’s alleged crimes matches the original, and how much it may have been adjusted for concealment. His narrative aligns with the official versions on the main points, even though it differs in detail.

Controversies Surrounding the Rakronnaret Case

Prince Rakronnaret became the focus of a disputed episode in which political ambition, corruption, homosexuality, and violations of social norms were closely entangled. Most scholarship on his fate relies on official, edited records compiled by the son of a government official. These texts describe the reign of King Rama III, but they foreground the political rationale for the execution and give little attention to the prince’s private life. His sexual conduct is mentioned only briefly and is rarely framed as directly related to the charge of treason against the state.

The execution is commonly explained through Rakronnaret’s ambition, corruption, and “improper behaviour.” A basic question remains, however: was any one of these factors, on its own, sufficient to justify such a brutal punishment? Rama III is known to have been aware of the prince’s violations for an extended period, yet he did not act decisively.

Rakronnaret sought to become the king’s heir. Rama III, however, did not appoint a successor, leaving the situation unresolved. Although he did not publicly name anyone, his sympathies apparently leaned toward Prince Mongkut, who at the time was a monk. In place of formal recognition as heir, Rakronnaret received a high rank and broad authority. He then used these powers for personal gain: he engaged in corruption, issued unjust rulings, and attempted to strengthen his claim to the throne.

When the king learned the full scale of these abuses, the case reportedly shifted in character. Beyond corruption, the prince was said to neglect his wives and concubines, preferring the company of male actors. This behaviour, combined with his claim to the throne, became part of the accusations of treason that culminated in his execution.

Some researchers argue that the decisive issue was not sexual behaviour as such, but the breach of a core social norm in Siamese society. Family ties carried substantial weight, and the prince’s refusal to maintain relationships with his wives could be interpreted as a challenge to the established order.

Family Ties as the Basis of Legitimacy

In Siam, family relations had direct political significance. The wives and concubines of rulers signalled loyalty not only to the husband, but also to his authority, while marriage reinforced ties between elite groups. The nobility followed similar rules: the most influential families were connected through kinship and marital alliances. Rakronnaret’s departure from these norms weakened his political legitimacy.

The historian Pramin Hruathong, analysing three sources, argued that neither corruption nor the prince’s preference for relationships with men could, by itself, have warranted a death sentence. Corruption was widespread among the nobility, and Rakronnaret’s private life, while discussed, was not treated as uniquely unusual: he had eight children, and he had met his duty to the family before ending relations with his wives.

The prince’s preferences were not secret to the king or the court. However, his demonstrative conduct, which exceeded accepted boundaries, could provoke irritation and resentment. Even so, Pramin argues that the principal reason for the execution was Rakronnaret’s ambition and his drive to seize power. The prince sought support among the nobility, members of the royal family, and the military - a development perceived as a serious threat to Rama III.

Sexuality and the Charge of Treason

The scholar Tamara Loos, by contrast, argues that the connection between Rakronnaret’s sexuality and the accusations of treason should not be dismissed. There is no direct proof that his preferences were decisive in his execution, but their relevance still matters: these themes recur in both primary and secondary sources.

In Siam at the time, the law tightly regulated the sexual lives of elite women, while rules for high-status men were less clearly defined. A nobleman’s power and standing depended largely on his ability to form marriages with the daughters of influential families. Rakronnaret disrupted this logic: he distanced himself from his wives and children and created a male “harem”. This weakened the marriage - political ties that secured the support of patrons. According to the sources, the prince did not even remember the names of all his children.

Marriage alliances required not only a formal union, but also sustained attention. Rakronnaret neglected this obligation in favour of the actors in his troupe. Kulap notes that the prince’s actors exploited their status, took bribes, and threatened plaintiffs who refused to pay.

Whenever the actors had legal cases, they set out in a boat with a golden roof, rowed by no fewer than 25 oarsmen… When provincial farmers and peasants, or Chinese merchants, saw this troupe, they feared it like demons. Yet these actor-demons did not eat the flesh of animals — they fed only on bribes.

— K.S.R. Kulap Kritsananon on Prince Rakronnaret’s troupe

In Tamara Loos’s view, the accusations of treason concerned not only politics, but also departures from established norms. The diversion of attention and wealth toward performers was framed as wasteful and as a threat to the existing system.

In that period, men could have relationships with partners of any gender, but usually within a hierarchy: the older, higher-ranking man assumed the active role, while the younger or lower-status partner assumed the passive one. Such relationships typically coexisted with heterosexual marriages.

Kulap and official documents quote the king’s warning to follow social norms: “do not give people grounds to slander you; do not disgrace your name in the kingdom by not living with your children and wives.”

Rakronnaret violated this arrangement. He openly preferred men and refused to live with his wives and children. One of his lovers was an actor who played the heroic character Inao - a symbol of traditional masculine identity. (Inao - a famous hero from Siamese/Thai court drama, associated with idealised masculinity.)

At the same time, the absence of reliable sources - including the questionable nature of Kulap’s writings - makes firm conclusions about the reasons for the execution difficult. Even so, the Rakronnaret case remains distinctive as an early, and very likely the first documented, episode in Thailand’s queer history.

P.S. Prince Rakronnaret’s residence was demolished; today, the area where it once stood is part of Saranrom Park.

Rakronnaret’s Lineage and Descendants

Kraison became the founder of the Phuengbun family line, which was officially recognised during the reign of King Rama VI. Unlike many other lineages, its name is not derived from the founder’s personal name. Kraison had several wives, but their names have not been preserved. He had 11 children. Among his known descendants are Field Marshal Chaophraya Ram Rakhop and Major General Phraya Anurit Thewa.

📣 Subscribe to our Telegram channel (in Russian): Urania. With Telegram Premium, you can translate posts in-app. Without it, many posts link to our website, where you can switch languages — most new articles are published in multiple languages from the start.

References and Sources

- Loos T. Strange bedfellows: male homoeroticism and politics in Thai history. Sexual Diversity in Asia. 2012.

- Проблемы литератур Дальнего Востока: труды X международной научной конференции / ред. А. А. Родионов. 2023. [Issues in the Literatures of the Far East: Proceedings of the 10th International Academic Conference, ed. A. A. Rodionov]

- Tags:

- Thai