Homosexuality in Ancient and Medieval Russia

Same-sex relationships and how they were viewed from Kievan Rus to Peter the Great.

- Editorial team

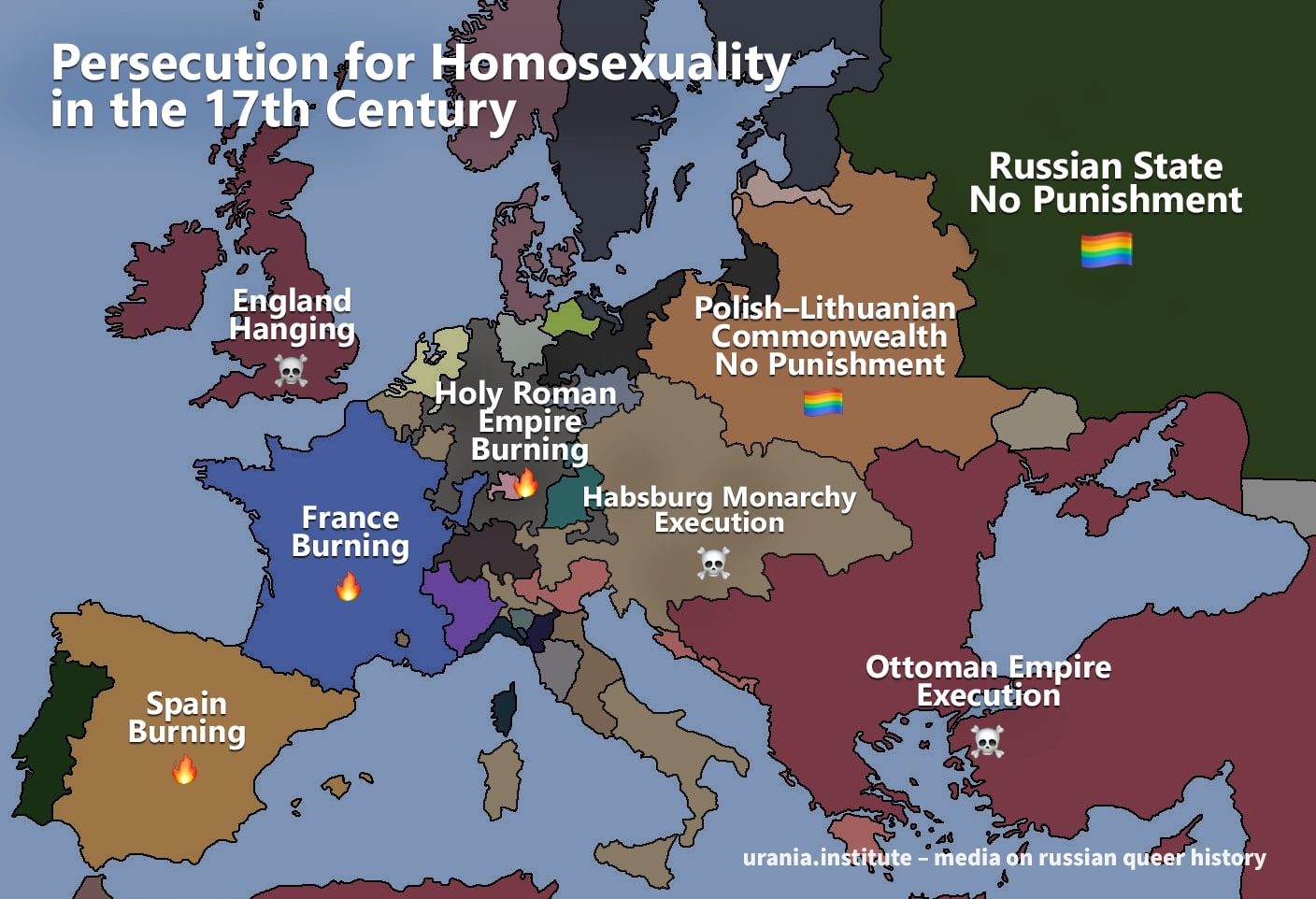

While in England, the Netherlands, France, and Spain, people were tortured and even burned at the stake for homosexuality, in Rus’ (a medieval East Slavic polity, not identical to modern Russia), there was not a single secular law up to the 18th century that explicitly punished people for the “sin of Sodom.”

At the same time, it is important to understand that the absence of a specific article in secular law did not mean full approval. In ancient and medieval Rus’, condemnation of same-sex relations appears in church rules: the Church regarded them as a sin and could impose epitimia (literally “penance”) — ecclesiastical repentance and restrictions for a believer.

The degree of persecution for homosexual relations varied across different historical periods. It depended on many factors: how visible the practice was, prevailing social attitudes, what the state authorities thought and did, the broader level of culture, and which social policies and values were considered paramount at the time.

In many periods of Russian history, attitudes toward homosexuality were milder than in a number of other countries. But it was not a straight line of “always tolerant” or “always strict.” Rather, it was wave-like — from relatively calm attitudes to harsh punishments.

Overall, the ancient and medieval periods of Russian history can be described as eras of “mild condemnation.” The state did not single same-sex relations out as a separate criminal issue; moral judgment and “sanctions” came mainly through religious norms and social ideas about what was permissible.

Norms and ideas about sexuality in Kievan Rus’

In Kievan Rus’ (a medieval state centered on Kyiv, c. 9th–13th centuries), views of sexuality and relationships were shaped by two different traditions. On the one hand, older Slavic pagan customs persisted, in which sexual freedom could be treated as a natural norm. On the other hand, a Christian worldview gradually took hold, in which sexual relations before marriage were considered sinful. As a result, the same situation might be viewed differently: acceptable by older custom, condemned by church norms.

According to research by M. A. Koneva, the spread of same-sex relations in Rus’ can also be explained by constant warfare, which kept men away from women’s company for long periods.

In the earliest secular law code of 11th-century Kievan Rus’, the Russkaya Pravda (literally “Rus’ Justice” or “Rus’ Truth”), homosexuality is not mentioned at all.

Clear attempts to regulate sexual life appear first in church sources — in the Kormchie books (literally “Pilot’s Books” or “Helmsman’s Books”, 12th–13th centuries). These were compilations of church rules and laws used by clergy and ecclesiastical courts. Same-sex relations were described with the broad term sodomy (sodomiya) — a word that, in the Old Russian church tradition, could refer both to same-sex contact and to other forms of forbidden sexual behavior (for example, masturbation). Punishments could vary: from mandatory repentance to a temporary ban from receiving communion.

Saint Boris’s “beloved youth”

The early-20th-century Russian philosopher Vasily Rozanov wrote that one of the first “documented” references to same-sex relations in Kievan Rus’ can be found in The Tale of Boris and Gleb, an Old Russian work about Princes Boris and Gleb, sons of Prince Vladimir, who were later venerated as holy passion-bearers — people who accepted death without resistance.

In the Tale, there is mention of Prince Boris’s “beloved youth” — a young man named George, originally from Hungary. The word otrok in Old Russian could mean a young person: an adolescent, a youth, or a young attendant at a prince’s court. As a sign of special favor, the prince gave him a gold grivna (not currency in this context) — a decorative neck ring worn as a collar.

The subsequent events are tied to the struggle for power after Prince Vladimir’s death. In 1015, the men of Prince Sviatopolk — whom the chronicles call “the Accursed” — attacked Prince Boris’s camp and pierced his body with swords. Then the following happened:

“Seeing this, the youth covered the body of the blessed one [that is, Boris] with his own, crying out: ‘I will not leave you, my beloved lord — where the beauty of your body withers, there I too shall be granted to end my life!’”

— “The Tale of Boris and Gleb”

After this, the killers stabbed the youth George as well. Then they tried to remove the gold grivna from his neck. They could not do it at once, because the ornament sat tightly and was very strong. So they cut off George’s head to take the precious item.

The Life of Moses the Hungarian: chastity, violence, and possible sexual meanings

Moses the Hungarian (Moisei Ugrin) was a Hungarian from Transylvania. In his youth, he served Prince Boris together with his brother George — the same George called the prince’s “beloved youth” above. When Prince Boris was killed, Moses survived and later hid with Predslava, the sister of the future Prince Yaroslav.

In 1018, when the Polish king Bolesław I (Bolesław the Brave) took Kyiv, Moses was captured and taken to Poland. There he was sold into slavery to a noble Polish woman. She burned with passion for Moses, who “stood out for his strong build and handsome face,” while he himself remained indifferent to women.

For a full year the Polish woman tried to force intimacy, resorting to various tricks: she “dressed him in costly garments, fed him exquisite foods, and, lustfully embracing him, urged him to intercourse.” Moses rejected her advances, tore off the fine clothes, and categorically refused to marry. His reply was:

“…and if many righteous men have been saved with their wives, I, a sinner, alone cannot be saved with a wife.”

— Dmitry of Rostov. “The Life of Our Venerable Father Moses the Hungarian”

One day she “ordered Moses to be forcibly laid upon her bed, where she kissed and embraced him; yet even by this she could not draw him to it.” Enraged by his refusals, she ordered him to be beaten every day, inflicting a hundred wounds. Finally, she commanded that Moses be castrated.

Later, during a revolt, he managed to escape and return to Kyiv. There he became a monk of the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra (the Monastery of the Caves, a major Orthodox monastery in Kyiv). The Orthodox Church canonized Moses as a model of chastity.

However, Rozanov believed that behind the familiar canonical form of the hagiographic text lies the story of a person with a different sexual orientation — punished for refusing a heterosexual marriage. He suggested that the Life can be read as an account of someone who experiences an inborn — and seemingly insurmountable — aversion to women. On this basis, Rozanov classified Moses as what was then called an “urning,” an early-20th-century term for a man with a homosexual orientation.

Same-sex relationships in Muscovite Rus’

Information about same-sex relationships in Muscovite Rus’ (the Moscow-centered Russian state, c. 15th–17th centuries) has come down to us mainly through church texts and the notes of foreign travelers.

Most church epistles — except for the Stoglav (literally “Hundred Chapters”) — did not carry the force of secular law. They were moral instructions and sermons aimed at maintaining a “proper” way of life from the perspective of the Orthodox Church. For example, in the widely circulated guide to everyday and religious life, the Domostroi (literally “Household Order” or “Domestic Order”), the “sin of Sodom” is condemned alongside other sins: gluttony, drunkenness, breaking the fast, witchcraft, and the performance of so-called demonic songs. Same-sex relations were presented as part of a general catalog of moral deviations, not as a distinct crime.

The priest Sylvester, one of the prominent church figures of the 16th century, wrote angry sermons against court youths whom he considered effeminate. He condemned young men who shaved their beards, used cosmetics, and — at least in his view — violated traditional masculine appearance. In his Epistle to Tsar Ivan Vasilyevich (the Terrible), Sylvester also accused the Russian army during the Kazan campaign (a major campaign against the Kazan Khanate, ending with the capture of Kazan in 1552) of spreading the “sin of Sodom,” linking military failures and moral decline with sinful conduct.

In the second half of the 15th century, the Kormchie books began to include a special sermon against “unnatural vices.” In it, the author demanded the death penalty for muzhelozhstvo (literally “lying with a man”), i.e., male–male sexual intercourse, as well as for blasphemy, murder, and violence, stressing that such deeds should receive no mercy. However, this was a sermon — an expression of moral outrage — not binding church or state law. Calls of this kind had no direct legal force.

One of the most active denouncers of the “sin of Sodom” in the early 16th century was Daniil, the Metropolitan of Moscow (a senior Orthodox bishop; head of a major church province). In his admonitions he condemned not only men living with “fornicating women,” but also effeminate youths who, as he wrote, “…envying women, transformed their manly face into a woman’s. Or do you wish to be a woman entirely?” He described in detail how they shaved their beards, plucked hair, used perfumes, and repeatedly changed outfits throughout the day.

In one sermon, Metropolitan Daniil told the story of a nobleman who, according to him, had become so entangled in same-sex relationships that he came to him for spiritual help. The man confessed that he could not rid himself of feelings for his beloved, because his passion felt too strong and irresistible. Daniil treated this state as the result of demonic influence and advised avoiding not only women, but also the youths who provoke “unclean thoughts.” For monks, he even proposed an extremely radical method of fighting temptation — self-castration — seeing it as a way to achieve complete deliverance from carnal desire. This, of course, was advice intended only for monks.

The first time same-sex relations were directly addressed in an official normative document is connected with the adoption of the Stoglav in 1551 under Ivan the Terrible. The Stoglav was a church–state compilation of one hundred chapters regulating matters of faith, ritual, and morality. It condemned the “sin of Sodom” as a grave violation of Orthodox norms, yet still allowed the possibility of repentance and correction. The minimum “punishment” was voluntary confession, fasting, and a change of lifestyle. In more serious cases, a person could be temporarily excommunicated or forbidden to attend services, though even these measures could be lifted upon sincere repentance. Thus, the most severe consequence was spiritual death — the loss of communion with the Church — rather than physical punishment.

The Stoglav also drew attention to the practice of monks keeping young attendants. This was considered potentially dangerous from a moral standpoint. The document explicitly forbade monks to “keep beardless lads alone,” and recommended that, if servants were necessary, they should be older and bearded.

Finally, it is important to remember that in this period the term sodomy was far broader than it is today. It could refer not only to male same-sex relations, but to any sexual practices not connected with procreation: bestiality, masturbation, and anal sex with a woman. Therefore, mentions of “sodomy” in sources do not always refer specifically to homosexuality.

The Novgorod petition of 1616

One of the rare Russian documents directly connected with the topic of same-sex relations was found in a Swedish archive and published in the early 1990s. It is a Novgorod chelobitnaya (literally “a beating of the forehead [to the ground]”) — a written complaint-petition to the authorities — drawn up on January 5, 1616, in Veliky Novgorod (“Great Novgorod,” a major city in northern Russia). At that time, the city was under occupation by Swedish troops, which is why the document later ended up in Sweden.

The author of the petition accuses a certain Fyodor of having, four years earlier, taken advantage of his childhood and coerced him into same-sex relations. Now, the petitioner says, Fyodor is threatening to tell his father and is blackmailing him, demanding a large sum of money in exchange for silence.

What is distinctive about the petition is that the complaint is aimed not so much at the fact of “sodomy” itself as at the experience of violence, deception, and extortion.

“…Fyodor sent me raisins and apples, saying, ‘These are presents for you from me’; and I, Your Majesty, at that time was foolish and small and mute, and I took his raisins and apples; and I, Your Majesty, believed that he truly was sending me raisins and apples as gifts. And I began, Your Majesty, to think that this Fyodor was drawing close to me [seeking friendship], and he wished to commit an indecent act with me, so that I would commit an indecent act with him; and I, Your Majesty, at that time was foolish and small and mute, and I did not dare tell my father; and I, Your Majesty, against my will committed fornication with him.

And when, Your Majesty, I became bigger [grew older], and my wits, Your Majesty, increased, then I, Your Majesty, said to him at that time: ‘Go away from me, Fyodor, be gone.’ And he, Your Majesty, grew rude, and he caused my father a loss, having it, Your Majesty, assessed against me in Great Novgorod — without cause — at thirty-eight rubles. And for me, Your Majesty, being in a foreign town, I did not wish to quarrel with him; I reconciled with him, and I gave him, Your Majesty, three rubles of money for nothing; and altogether, Your Majesty, this loss in Great Novgorod came to me … [the text continues with an unclear accounting phrase about a “surety/guarantor” and eight rubles].”

— “Petition about being forcibly induced to sodomy, with a complaint against a certain Fyodor” (missing beginning). January 5, 1616

How the story ended, and whether Fyodor was punished, is unknown.

Foreign observers on “sodomy” in Muscovy

A great deal of information about same-sex relations in 16th-century Muscovy was recorded by foreign visitors to Russia, as well as by authors who compiled reports from ambassadors and merchants. These descriptions matter not only as “outside” accounts, but also as evidence that same-sex relations were visible enough to attract the attention of many travelers.

In 1551, the Italian historian Paolo Giovio published a series of books, Descriptions of Men Famous for Martial Valor. Relying on stories from Russian ambassadors and merchants, he described the Muscovite state in the time of Vasily III and mentioned same-sex relations among Russians, linking them to an “entrenched custom” and comparing them to “the manner of the Greeks”:

“…according to a custom long rooted among the Muscovites, it is permitted, in the manner of the Greeks, to love youths; for the noblest among them — and all ranks of the knightly estate — are accustomed to take into their service the children of respectable townsmen and instruct them in the military arts.”

— Paolo Giovio. “Descriptions of Men Famous for Military Valor.” 1551

The remark about “the Greeks” reflects a stereotype widespread in Europe at the time: in Western tradition, Byzantium and the “Greek world” were often portrayed as especially licentious.

The researcher I. Yu. Nikolaeva offers an interpretation of why same-sex practices and “indecent” passions appear so insistently in European travel accounts. In her view, it was not only that visitors looked at a foreign country with a moralizing gaze. She also argues that in Muscovy this sphere remained outside harsh criminal repression longer than in Western Europe, where such actions often led to severe punishment. Nikolaeva puts it this way:

“…it is precisely for this reason that in virtually all foreigners’ accounts attention is drawn to the Muscovites’ ‘indecent’ passions: in Russian society this phenomenon was not repressed to the extent it was in Western Europe, where a more favorable socio-psychological climate developed for corresponding cultural-psychological mutations.”

— I. Yu. Nikolaeva. “The Problem of Methodological Synthesis and Verification in History in the Light of Contemporary Concepts of the Unconscious.” 2005

The English poet George Turberville, who arrived in Russia in 1568 as part of a diplomatic mission, described his impressions in poetic letters. In one letter to a friend he also noted the existence of homosexuality among Russians and wrote about it with condemnation and astonishment:

“The monster more desires a boy within his bed,

Than [than] any wench, such filthy sinne [sin] ensues a drunken head.”

— George Turberville, English poet

The Swedish diplomat and historian Petrus Petreius (Peter Petrei de Erlezunda), who served four years as an envoy in the Russian state, wrote that same-sex relations were found among Russian boyars (high-ranking hereditary nobles in medieval/early modern Russia) and the gentry: “…especially the great boyars and nobles commit… sodomitic sins, men with men.”

He was particularly outraged that these “sodomitic sins” went unpunished and did not provoke public condemnation. He claimed that “…boyars and nobles… consider it an honor to do this [male intercourse], without shame and openly.”

A similar claim about comparative tolerance was made by Samuel Collins, an English physician at the court of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich. Speaking of “sodomy and male intercourse,” he emphasized that in Russia it was treated more leniently than in England because, as he wrote, “it is not punished here by death.” Collins even asserted that Russians are “inclined to it by nature.”

The same kind of outrage appears in the words of Yuri Krizhanich, a Croatian priest who lived in Russia in 1659–1677:

“…here, in Russia, they simply joke about such a loathsome crime, and nothing is more common than that, publicly, in jesting conversations, one boasts of the sin, another reproaches someone else, a third invites another to the sin; all that is lacking is that they commit this crime before all the people.”

— Yuri Krizhanich, a Croatian priest who lived in Russia in 1659–1677

These conclusions reflect a typical early modern habit of explaining behavior through “national character,” supposedly innate traits of a whole people. Still, the fact that travelers returned to this topic again and again suggests that, for European observers, it was conspicuous — and, in their eyes, it distinguished Muscovy from the Western European world they knew.

In Western Europe in the 16th–17th centuries, same-sex relations were prosecuted as a criminal offense, and punishments could be extremely brutal — up to the death penalty, including burning at the stake. Against that background, it becomes clearer why many foreigners were indignant that in Russia such “sins” could remain unpunished.

An additional layer of perception mattered as well: Europeans often portrayed Russians stereotypically — as “savages,” pagans, and “schismatics,” as people seen as apostates from the “true” faith. Such labels intensified negative attitudes toward Muscovy and sharpened moral accusations. Protestants in particular sometimes spoke harshly about Russia, calling Russians “the most irreconcilable and terrible enemies of Christianity.”

Before Peter the Great

By the end of the Muscovite period, the Russian Tsardom adopted a major new law code — the Sobornoye Ulozhenie (the “Council Code” of 1649). This document became the foundation of legislation for almost two centuries and remained in force until 1835. It contains no mention of homosexuality. Questions of same-sex relations remained primarily within religious and moral frameworks.

At the same time, Russian society had been aware of same-sex relations since early times. But it would be wrong to speak of full tolerance. Same-sex relations were condemned, yet more often remained within the sphere of moral supervision, church admonition, and a religious understanding of sin — rather than strict legal regulation.

Female homosexuality in that era was often perceived as a form of masturbation rather than as an independent type of relationship. Because patriarchal ideas did not treat women as equal members of society, sexual relations between women drew less attention from both society and the state. As a result, few sources survive that describe female homosexuality in Russia of that period in detail.

Discussion of same-sex relationships does not disappear later either: already at the turn of the 17th–18th centuries, at the beginning of the Petrine era, the Jesuit Franciscus Emilian wrote in a report from 1699:

“The boyars who returned from our lands brought many foreigners with them, among whom the greatest trouble has been caused us by the young men of our faith, because they were corrupted. These sins that cry out to heaven are very common here, and no more than four months ago some boyar, at table and in company, boasted that he had corrupted only 80 young men.”

— Franciscus Emilian. Report. 1699

The first criminal punishment for same-sex relations in Russia — though only in the army — was introduced by Peter the Great, under the influence of Western European legal ideas that he actively borrowed while restructuring the state and the military.

📣 Subscribe to our Telegram channel (in Russian): Urania. With Telegram Premium, you can translate posts in-app. Without it, many posts link to our website, where you can switch languages — most new articles are published in multiple languages from the start.

🇷🇺 This piece is part of the article series “LGBT History of Russia”:

- Homosexuality in Ancient and Medieval Russia

- A Cross-Dressing Epic Hero: the Russian Folk Epic of Mikhaylo Potyk, Where He Disguises Himself as a Woman

- The Homosexuality of Russian Tsars: Vasily III and Ivan IV “the Terrible

- Uncensored Russian Folklore: Highlights from Afanasyev’s “Russian Secret Tales

- Homosexuality in the 18th-Century Russian Empire — Europe-Imported Homophobic Laws and How They Were Enforced

- Peter the Great’s Sexuality: Wives, Mistresses, Men, and His Connection to Menshikov

- Russian Empress Anna Leopoldovna and the Maid of Honour Juliana: Possibly the First Documented Lesbian Relationship in Russian History

- Grigory Teplov and the Sodomy Case in 18th-Century Russia

- Russian Poet Ivan Dmitriev, Boy Favourites, and Same-Sex Desire His the Fables ‘The Two Doves’ and ‘The Two Friends’

- The Diary of the Moscow Bisexual Merchant Pyotr Medvedev in the 1860s

- Maslenitsa Effigy: The “Man in Women’s Clothes” of Russia’s Pre-Lent Carnival

- Sergei Romanov: A Homosexual Member of the Imperial Family

- Andrey Avinoff: A Russian Émigré Artist, Gay Man, and Scientist

References and Sources

- Димитрий Ростовский. «Житие преподобного отца нашего Моисея Угрина». [Dimitrii Rostovskii – The Life of Our Venerable Father Moses the Hungarian]

- Домострой. Памятники литературы Древней Руси. Середина XVI века. 1985. [Domostroi]

- Емченко Е. Б. Стоглав: исследование и текст. 2000. [Emchenko, E. B. – The Stoglav: Study and Text]

- Горсей Дж. Записки о России, XVI – начало XVII в. 1990. [Jerome Horsey – Notes on Russia, 16th–Early 17th Centuries]

- Гудзий Н. К., сост. Хрестоматия по древней русской литературе XI–XVII веков для высших учебных заведений. 1952. [Gudzii, N. K. – Reader in Old Russian Literature (11th–17th Centuries) for Higher Education]

- Жмакин В. И. Митрополит Даніил и его сочиненія. 1881. [Zhmakin, V. I. – Metropolitan Daniil and His Writings]

- Жмакин В. И. Русское общество XVI века. 1880. [Zhmakin, V. I. – Russian Society in the 16th Century]

- Кон И. С. Лунный свет на заре: лики и маски однополой любви. 1998. [Kon, I. S. – Moonlight at Dawn: Faces and Masks of Same-Sex Love]

- Конева М. А. Преступления против половой неприкосновенности и половой свободы, совершаемые лицами с гомосексуальной направленностью: автореферат диссертации. 2002. [Koneva, M. A. – Crimes Against Sexual Integrity and Sexual Freedom Committed by Persons with a Homosexual Orientation: Dissertation Abstract]

- Кудрявцев О. Ф. Россия в первой половине XVI в.: взгляд из Европы. 1997. [Kudriavtsev, O. F. – Russia in the First Half of the 16th Century: A View from Europe]

- Материалы из шведского архива: Riksarkivet, SE/RA/754/2/VII, no. 1282, f. 23. [Riksarkivet: Swedish Archival Materials (SE/RA/754/2/VII, no. 1282, fol. 23)]

- Николаева И. Ю. Проблема методологического синтеза и верификации в истории в свете современных концепций бессознательного. 2005. [Nikolaeva, I. Iu. – Methodological Synthesis and Verification in History in Light of Modern Concepts of the Unconscious]

- Павлов А. С., ред. Памятники древнерусского канонического права. 1908. [Pavlov, A. S. – Monuments of Old Russian Canon Law]

- Письма и донесения иезуитов о России конца XVII и начала XVIII века. 1904. [Letters and Reports of Jesuits on Russia (Late 17th–Early 18th Centuries)]

- Розанов В. В. «Люди лунного света». 1911. [Rozanov, V. V. – People of Moonlight]

- Collins, S. The Present State of Russia. In a Letter to a Friend at London; Written by an Eminent Person residing at the Great Czar’s Court at Mosco for the space of nine years. 1671.